The 7th Armoured Brigade

Engagements - 1942

During 1942 the 7th Armoured Brigade was involved in the following battles and campaigns. These include Preparations for the Far East, Japanese Invasion of Burma, Fight for Burma (including First Encounters, Withdrawal to Rangoon, Rangoon to the Irrawaddy, Battle of of Yenaungyaung, Final Stand in Burma, Crossing the Chindwin and back to India and India and then to Iraq).

After the end of Operation Crusader, in November 1941, 7th Armoured Brigade was withdrawn from the line for re-equipping and at this time it became known that it was destined for the Far East theatre of war, following Japan's entry into the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7th December 1941.

At this time the Brigade, under the command of Brigadier J. Anstice DSO, consisted of 7th Queen's Own Hussars (commanded by Lt-Col F. R. C. Fosdick, 2 i/c Major Roland Younger), 2nd Bn. Royal Tank Regt (initially commanded by Lt-Col R. F. Chute DSO, and the later in March 1942, Lt-Col G. F. Yule), the 414 Battery RHA (Essex Yeomanry, 104th RHA) equipped with twenty-four 25-pounder guns, plus RAOC and RASC support troops. Both armoured regiments were equipped with fairly new American Stuart (Honey) light tanks, numbering 115 tanks in total. The Brigade set sail aboard 7 transport ships. The 'A' vehicles were in HMT Mariso, HMT Birch Bank, HMT African Prince and HMT Trojan. Most of the personnel of 2nd RTR were aboard HMT Ascanius. This was to be a voyage of 4,600 miles through the Suez Canal and Red Sea to Aden, and eventually across the Indian Ocean to Rangoon. Initially the convoy was destined for Singapore, but when Malaya was attacked by the Japanese at the same time as Pearl Harbor on 7th December 1941, and the situation in Johore became desperate in mid-January 1942, the Brigades convoy was diverted on the orders of General Wavell had diverted from its route to Java and reached Rangoon on the 20th February 1942. By now the brigade had adopted the Jerboa divisional sign, but with the background colour changed to jungle green, as shown below, with the shoulder flashes shown at the top of the page. All these had previously been red prior to the move to the Far East.

The Japanese had started their advance towards Burma from Siam (now called Thailand) on 16th January 1942 , quickly taking Kawkareik and then capturing Moulmein, 100 miles due east of Rangoon across the Gulf of Martaban. Most of the The Burma Rifles garrison had escaped from Moulmein by ferry on 21st January 1942.

After its arrival the Brigade quickly discovered that Burma was definitely not good tank country. The region has two substantial rivers running north and south, with the first being the great Irrawaddy and, 50 miles to the east, the Sittang. The few roads and tracks that there were went through rice paddy fields, and were mostly underwater in the rainy season and then baked hard in summer, having, many banks and obstructions. Beyond the paddy fields was the jungle, which was almost impenetrable for tanks. Further into Burma, during the retreat between Kyaikto and Mokpalin on the east side of the Sittang River, those taking part found that the single unsurfaced track, was pock-marked with bomb craters and barely wide enough for one vehicle to pass another. Any vehicle carrying wounded was given priority, but the track was hedged in by jungle so thick that men easily became lost if they wandered far from the track. The commanders on the ground found it difficult to maintain command of any unit much larger than platoon, due to the poor communications as there were no 'walkie- talkies' and communication relied mainly on 'runners' of which many lost their way. It was blazingly hot and water bottles were soon emptied. No one knew anything about the enemy was and every now and again the Japanese would make surprise night mortar attacks only vanish into thin air, afterwards.

The breakdown in communications meant that 17th Indian Division HQ was out of touch with its own brigades and with Burma Army HQ, too. The three British-Indian brigades of 17th Indian Division were forced back from the River Bilin line 70 miles north-west of Moulmein and had to fight their way through dense jungle and rubber plantations to Kyaikto. Their attackers in the form of the Japanese 213th and 214th Infantry Regiments managed to reach Mokpalin 3 miles south of the huge 500-yard long vital bridge across the River Sittang. Here the British-Indian 46th and 16th Brigades were surrounded, and the bridgehead defenders were attacked on their right flank by the Japanese 215th Infantry Regiment. It was now a terrible but necessary decision had to be made by GOC 17th Indian Division, (Major-General Jacky Smythe) to either blow the bridge and sacrifice the bulk of his division, your to risk it being captured intact by the Japanese, which would lay the way to Rangoon open to the enemy! In a still controversial decision today, but the bridge was blown on 23rd February 1942 and out of the Divisions original 12 battalions only 80 British officers, 69 Indian and Gurkha officers and 3,335 other ranks escaped. Winston Churchill, himself wrote that 'this was a major disaster.'

The 7th Armoured Brigade (The Green Jerboa) in the fight for Burma

By now that Singapore had fallen more pressure was to be put on the defenders of Burma and although reinforcements including the 7th Armoured Brigade and two additional squadrons of Hurricanes were soon to reach the area. Winston Churchill regarded Burma and contact with China as the most important feature in the whole Eastern theatre of war, however apart from the survivors of the 17th Indian Division there was only the 1st Burma Division left to try and defend the whole of Burma. The 7th Armoured Brigade convoy arrived in Rangoon harbour two days before the disaster of the Sittang bridge and at this stage the only the defence line between the Japanese and Rangoon was that of the Pegu river. Here the remnants of the 17th Indian Division with their 1,400 rifles and a few machine guns were joined by three British battalions from India and by 7th Armoured Brigade. Although they did not know it the time the men of 7th Armoured Brigade were to play an important part in the fighting that was to follow.

When the convoy arrived it was met by Brigadier Anstice who had flown on ahead. He briefed his senior officers on the situation and on the enemy forces. This included the information that the Japanese did not have an adequate anti-tank gun, and that their Type 94 Tankette, Type 95 light tanks were few in numbers and of poor quality. Burmese dock labourers had fled a few after days of Japanese bombing, and so the unloading of tanks, lorries, guns, ammunition and other supplies had to be was carried out by the troops. While this was happening Captain Reverend Metcalfe, the 7th Hussars' chaplain, visited Rangoon Zoo in search of fresh meat. All he found a Boa constrictor, a crocodile and a lively orangutan, but abandoned RAF lorries and plenty of cigarettes and spirits from bonded warehouses along the docks were soon 'discovered'. The Brigade leaguer was initially established in a large rubber plantation 15 miles north of Rangoon.

First Encounters: The Japanese XV Army, under General Iida, consisting of two divisions, the 33rd and 55th Infantry, had initially been thwarted by the demolition of the key Sittang bridge, but now it had moved north to Kunzeik and Donzayit respectively without any opposition. Here they crossed the River Sittang by ferry heading west and south towards Rangoon. Meanwhile. the remnants of the 17th Indian Division were reforming around Pegu. Now 7th Armoured Brigade was soon in action, with 'B' Squadron 2 RTR (commanded by Major J. Bonham-Carter) moving forward on 23rd February to Waw, 20 miles north-east of Pegu and 'C' Squadron (commanded by Major M. F. S. Rudkin) taking over two days later. Here they burned the deserted village in order to defend a wooden bridge. The following night a Sergeant, from the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) disguised as a Burmese, who had escaped from the Sittang, and told 2nd RTR that two Japanese forces were on the move to outflank Waw. An hour later several hundred Japanese arrived at the canal, so the order for the bridge to be blown was given. The next day 'A' Squadron, 2nd RTR (commanded by Major N. H. Bourne), patrolling with the 1st Bn. The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) north of Payagyi, killed fourteen Burmese 'dacoits' (basically Burmese bandits) armed with Japanese weapons. On 1st March 1942, 'B' Squadron moved towards Tazon, and 'C' Squadron towards Waw. 2nd RTR Battalion HQ was moved to Payagyi, and re-equipped with No. 19 wireless sets. On 2nd March a Troop was patrolling an irrigation canal and came under heavy fire from 75mm guns that knocked out two Stuart tanks, killing two troopers and wounding another in a third tank.

With 1st Bn. West Yorkshires from 17th Indian Division, 2nd RTR were in action on 2nd March to try to recapture Waw village, but were unsuccessful. The Japanese resumed their offensive on the night of 3rd/4th March, and 'C' Squadron, 2nd RTR were attacked at first light in heavy mist. The Squadron's tanks were surrounded and over-run with yelling Japanese who advanced right up to the tanks. Some of them carried explosives attached to long poles which they attempted to drop into the turrets. However, the Stuarts Machine Guns and the tank commanders' Tommy guns produced deadly fire. Fortunately, 7th Hussars, who were due to relieve 2nd RTR, were now quite close, so Major Rudkin gave the order for each tank to find its own way back to RHQ across country. The going was extremely bad and obstacles were tackled for which the tanks could never have been designed. It was a nightmare journey as the tanks found it hard to pick a suitable route due to the mist. The situation was made worst by the occasional sniper who infiltrated across the road behind the tank whose shots kept the heads of the tank commanders down. Somehow every of 'C' Squadron's tanks arrived back safely although the crews were bruised and shaken.

Meanwhile 'B' Squadron 7th Hussars (commanded by Major G. C. Davies-Gilbert), had arrived in Payagyi to find the Japanese had already arrived there. One troop leader, noted that in the thick mist visibility was down to ten yards and wireless communication was appalling. 'B' Squadron HQ behind came was under attack from enemy ambush, the first of many the Brigade was to be involved in during the next few months. At about 11:00 'B' Squadron took up a position on the Payagyi crossroads to keep the village under observation, but it was now appallingly hot and as the crews could not dismount the felt like 'fried eggs in a pan.' Infantry assisted by 'A' Squadron, 7th Hussars (commanded by Major C. T. Llewellen Palmer), cleared Japanese infiltrators from a wood, and when two Type 95 Japanese tanks appeared in the areas and were engaged by the Squadron. Compared to the experienced tank crews of the Brigade the Japanese tanks seemed not to know how to move and operated and remained stationary in the middle of an open field. They were knocked out immediately before they knew 7th Hussars were there. The Japanese tanks were very much the same as the Honey (Stuart) and obviously copied from an American design and in fact carried cans of American oil.' Elsewhere Colonel Fosdick, CO 7th Hussars, had his Stuart tank hit by anti-tank fire which blew off a track, and a 'B' Squadron tank was also hit and disabled. A Troop from 'B' Squadron was send to assist 7th Hussars RHQ, but all three tanks were hit repeatedly by four anti-tank guns man-handled into position in the night. The Forward Observation Officer (FOO) of the Essex Yeomanry, put down a 'stonk' on the enemy position, and a tank from, 'A' Squadron, with a company of West Yorkshire infantry, mounted an attack which captured the Japanese anti-tank guns, inflicting heavy casualties. Soon three more Type 95 Japanese tanks approached and were engaged by two Troops from 7th Hussars in hull-down positions. Two of the Type 95s were knocked out at 1,000 yards range and the third abandoned by its crew.

Withdrawal to Rangoon: The 7th Hussars were ordered to retire through Pegu to rejoin the rest of 7th Armoured Brigade at Hiegu. When they arrived in the town as darkness was falling. The town had been severely bombed and the whole place was blazing from end to end and were lucky to still find the only bridge standing. Meanwhile the enemy had erected a road block three miles south west of the town and 7th Hussars halted while 'A' Squadron moved down to the block to ascertain its strength. It was apparent that it was quite impossible to get through and probes were made in various directions to get round the flanks, yield not alternative routes. Lt-Col Fosdick decided to move the regiment closer to the road block and leaguer for the night and due to Japanese small-arms fire and an expected night attack the crews had to stay in the tanks and spent one of the most harassing nights most would remember in the war.

Dawn was most welcome, with the only trouble coming from sporadic mortar fire. At an Orders 'O' group first thing in the morning decided that the block should be cleared by a company of infantry supported by one troop from 'A' Squadron. The small force set off after 7 a.m., and as when it reached the road they were submerged by a panic-stricken mob of refugees in complete disarray. It looked like the refugees would hamper the whole operation and it was impossible to move without running them down. Eventually 'A' Squadron' had to threaten to open fire, but the Japanese did the job for them. Along with an Officer from the Essex Yeomanry with us as OP and 'A' Squadron moved towards the road block an on On coming round a bend it suddenly came up against the road block which consisted of two lorries drawn across the road and another obstruction some 300 yards farther down the road. The country on either side was heavily wooded and there was no way round. The lorries were easily moved by the tanks, but immediately came under a hail of small-arms fire. The Troops from 'A' Squadron took up a fire position and saturated the whole area with the Brownings Machine Guns for ten minutes. While this was going on the infantry most gallantly cleared the block and the Essex Yeomanry put down a concentration on the area. During this engagement the Japanese threw some kind of Molotov cocktails at the tanks knocking out one. The force pushed on to the next block, fast under heavy fire and were relieved to find it clear. The infantry had provided gallant support and clearing the jungle on either side, although the company commander had been severely wounded during the engagement.

Having got through the road block the forces pushed on stopping a few miles up the road where it linked up with a patrol of 2nd RTR and another Troop from 7th Hussars which had escorted the Brigadier through the block the previous night. The lead Troop was not in not contact Squadron HQ, as the Troop commanders aerial had been shot away and was getting very worried about the rest of the column when it appeared behind them.

While the main force of 7th Hussars was fighting its way through the road block, its Chaplain Captain Reverend Metcalfe, was in Pegu with the Cameronians and West Yorkshires during their rearguard action. In this action both battalions suffered casualties and in the combined Regiment Aid Post (RAP) Captain Metcalfe and Padre Funnell had been helping the wounded all day under vigorous Japanese sniper fire. A convoy of wounded in ambulances and lorries set off with a rearguard of Cameronians under Major Magnus Grey, but as the did so heavy Japanese fire compelled Captain Metcalfe and Padre Funnell to take cover under the last few lorries of the convoy, all of which were quickly put out of action. Retreating down the road the ambulance convoy came upon the scene of the road block which had been broken earlier that morning by the tanks of 7th Hussars. It was a scene of indescribable carnage with burnt-out lorries piled together with the dead crews hanging grotesquely out of the driving cabs. At this moment a mortar shell hit the lorry blowing Captain Metcalfe into a ditch, although he escaped unhurt. Unfortunately, Padre Funnell was later ambushed and butchered in cold blood near Prome. For his deeds in evacuating the wounded from Pegu, Captain Metcalfe was awarded an immediate DSO.

The 7th Hussars were now ordered to proceed north to a rubber plantation near Taukkyon, Brigadier Anstice. General Harold Alexander had been sent by Winston Churchill to take supreme command of all forces actually in Burma and soon after his arrival on 5th March General Alexander realised that Rangoon was doomed and so he ordered all surviving forces to cut their way northward through many roadblocks to reach Prome 200 miles north of Rangoon. General Alexander also, reluctantly, gave the order for the destruction of the great oil refineries at Rangoon. However, the abrasive and difficult American general, Joseph Stilwell ('Vinegar Joe'), commanding the Vth and VIth Chinese Armies already in eastern Burma, disputed the command situation.

Rangoon to the Irrawaddy: Twenty-four miles north of the city at Taukkyan the Japanese 33rd Division, was moving swiftly from east to west in its drive to capture Rangoon and had erected a formidable road block across the main road. This road block consisted of two 75mm guns and several machine-guns firing from the flanks it was going to be a tough nut to crack. Waiting to get through the road block (as it could not be bypassed) were most of 17th Indian Division, all of 7th Armoured Brigade and General Alexander and his entire Army HQ. Lt-Col Fosdick, CO 7th Hussars, sent a Troop of 'B' Squadron with infantry support to clear the block. One Stuart tank was hit by a 75mm shell and the infantry took heavy casualties. The Essex Yeomanry guns then supported 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR, along with 1st Bn. Gloucestershire Regiment also they failed too. The situation appeared so bad that at one point General Alexander even suggested to Lieutenant-General Hutton that the British troops might disperse and try to fight their way north through the jungle. However, a third attack was planned for dawn with 'A' Squadron 7th Hussars, 1/10 Gurkhas, 1/11 Sikhs supported by RAF bombing and all artillery available. At first light on 8th March Major Bonham-Carter led 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR, towards the road block only to discover that the enemy had gone.

This was one of the classic military blunders of the war. General Iida's master plan was for Rangoon to be captured from the west and he was sure the British and Indian forces would stay and fight for Rangoon, as he would have done in similar circumstances. So after General Sakurai, GOC, the Japanese 33rd Infantry Division, had very efficiently blocked the main road, and after passing his whole formation across it at Taukkyan, he 'obeyed' his rigid orders and abandoned their roadblocks. When he arrived in Rangoon General Sakurai was astonished to the city undefended and empty. The British, and Indian formations retreating from Rangoon were equally surprised at being given a head start.

Most of 2 RTR were still in the Hiegu area south of Taukkyan as after 'B' Squadron's attack on the roadblock had failed, a possible escape route on foot to Bassein was being investigated. The hope was to find boats or a ferry there, but fortunately the need did not arise. Captain James Lunt, Burma Rifles, met a 2 RTR trooper and asked him how the fighting in Burma compared with his experiences in North Africa. '"Much the same amount of shit flying around, but the trouble with these Japanese bastards is that they don't run away like the Italians!'". On one occasion 414th Battery found Japanese Infantry had got behind their gun positions and were preparing for a bayonet charge, so the whole battery grabbed their rifles, turned around and kept firing until all the Japanese were killed!

The allies were fortunate that the Japanese did not press their northward retreat, as they needed time to rest after the severe fighting and heavy casualties and long marches they had made. The Burma division fought a steady delaying action back to Toungoo (100 miles north of Pegu) while the 17th Indian Division and the 7th Armoured Brigade moved by easy stages to Prome (70 miles west of Toungoo on the River Irrawaddy).

The main rearguard was formed by 2 RTR and during the next week the withdrawal continued via Gyobingauk, Paundge and Wettigan. On 13th March 1942 Lieutenant-General Bill Slim (later Viscount Slim of Burma and the commander of 14th Army), who had been appointed by Wavell as the new Corps Commander, arrived at Prome for his first conference with Major-General Bruce Scott, GOC, 1st Burma Division, and Major-General 'Punch' Cowan, GOC, 17th Indian Division. All three men had served together in the 6th Gurkhas and knew each other well. General Alexander then gave his orders to Slim's 1st Burma Corps.

Five days later 7th Armoured Brigade and 17th Indian Division halted in the Nattalin area (20 miles south-east of Prome) to cover the concentration of 1st Burmese Division at Prome. Meanwhile only one division of the Chinese V Army had reached Toungoo in the River Sittang valley, the rest of the V th and VI th Armies slowly following behind them. Many British Officers considered the Chinese as unreliable, as they had no logistics worth the name and time meant nothing to them, travelling the country like the Tartar hordes looting, stealing and burning. It was also common for any Chinese General not to carry out an order with which he disagreed. The Chinese discipline was rough and ready and very few Chinese spoke English, with no British troops speaking Chinese.

As the British and Indian formations would travelled along the road to Prome the 40-mile long convoy of 1,400 British and Indian vehicles were held up from time to time by roadblocks made up of tar barrels, felled trees and overturned captured lorries defended by field guns on both sides. Only determined 'hook' attacks around the flanks were likely to succeed. At this time Lieutenant-General Bill Slim visited all the troops under his command, including 7th Armoured Brigade, now under the command of 17th Indian Division, was delighted to see it and note its condition. Its two regiments of light tanks, American Stuarts (or Honeys) mounting only a 37mm gun and having very thin armour which any anti-tank weapon would pierce, were by no means ideal for the sort of close fighting the terrain required. However, any weakness in the tanks however was made up by the crews as both the 7th Hussars and 2nd Bn. Royal Tank Regiment were as good British troops as he had seen anywhere. Both Regiments had had plenty of fighting in the Western Desert before coming to Burma and they looked what they were - confident, experienced, tough soldiers. Their supporting units, 414 Battery, 104th (Essex Yeomanry) RHA, 'A' Battery 95th Anti-tank Regt RA and 1st Bn West Yorkshire Regt were up to their standard.

After his inspection General Slim made a careful assessment of the situation, including 'our first intimation of a Japanese move was usually the stream of red tracer bullets and the animal yells that announced their arrival on our flank or rear', and 'the Japanese were obviously able to move for several days at a time through jungle that we had regarded as impenetrable. They had developed the art of the road block to perfection. We seemed to have no answer to it'.

Slim now tried to concentrate his two divisions, with 17th Indian near and around Prome with 7th Armoured Brigade with the reserve infantry brigade in the rear at Nattalin. In Taungdwingyi were 75,000 gallons of high-octane fuel for the Stuarts and Slim thought that the country immediately south of Prome would be suitable tank country. On 20th March the Chinese Army launched an attack to prevent the Burma Road being cut, but four days later their 200th Division of V th Army in Toungoo was suddenly cut off by the Japanese 55th Division. On the 28th March General Alexander asked Slim to take the offensive to relieve pressure on the Chinese. General Cowan sent Brigadier Anstice with 7th Hussars, two troops of Essex Yeomanry, three infantry battalions, including the 1st Bn Gloucesters, to re-occupy Paungde and advance on Okpo, both on the main road and railway line 25 and 50 miles south of Prome. Two thousand Japanese held Paungde, and after initial success the British and Indian Brigade was driven out after inflicting heavy casualties. However, worse was to come as a strong Japanese force had appeared in Shwedaung only 10 miles south of Prome, thus cutting off Brigadier Anstice's withdrawal.

Two Indian battalions, from 17th Indian Division, were sent to clear Shwedaung from the north and just after 1800 hrs, on 29th March, the advance guard of Brigadier Anstice's force launched an attack, which failed, as were the two more that followed. However, during the morning of 30th March, 7th Hussars and supporting infantry burst through the Japanese road blocks in Shwedaung. They found that the town was burning furiously, with many trucks on fire as Japanese aircraft machine-gunned and bombed the allied convoys. In one action, the 7th Hussars were attempting to cross a bridge, under heavy fire from the Japanese, but, the bridge had become blocked with vehicles and tanks put out of action by gunfire. It was now that one tank commander (Sgt Hipsey) turned his tank around and re-crossed the bridge and began pushing the knocked out vehicles and tanks out of the way to enable the regiment to cross which they did. However, the Japanese concentrated on his tank and he and his crew were killed.

Several hundred Japanese and rebel Burmese were caught and killed, but the 7th Hussars lost 10 Stuarts, the Essex Yeomanry 2 guns, the column over 300 vehicles and the Infantry over 350 killed or wounded. The Dukes (2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellington's Regiment) suffered the worst, lost 5 officers and 117 other ranks.

Fierce fighting continued and 'C' Squadron, 7th Hussars, under Major Congreve, smashed through a road block and a Troop Commander (Lieutenant Palmer) managed to get through to Div HQ in Prome. However, another (Lieutenant Pattison MC) was taken from his knocked-out Stuart, was beaten and flogged with sticks and was tied to a road block. Fortunately when the bombardment to clear the road block stated the first 25-pdr shell to hit the roadblock actually enabled Lt. Pattison to escape in the darkness. Elsewhere two tanks, charged over a road bridge and crashed over the embankment, however, by 1400 hrs the battle was over and the remains of the column, assisted by 'A' and 'B' squadrons of 2 RTR, from the North, managed to break out as C' Squadron, 2 RTR had been send on a wild-goose chase to help a column of 1st Burmese Division on 28th March.

Meanwhile the Chinese 200th Division in Toungoo were still surrounded and had to fight their way to safety suffering 3,000 casualties and losing all their guns and vehicles and a general Chinese withdrawal took place towards Pyinmana. The Japanese now had total command of the skies although the remaining British-flown Hurricanes and American P40s put up a gallant defence with an estimated total of of 233 Japanese planes destroyed in the air and 58 on the ground. However, the main British airfields at Magwe and Akyab were put out of action by 150 Japanese bombers.

Battle of Yenaungyaung: It was now essential to deny the oil fields at Yenangyaung to the Japanese some 100 miles north of Prome. The allied lines of defence were planned to be from Minhia (west back of the river Irrawaddy) east to Taungdwingyi, and Pyinmana (an important rail junction 50 miles north of Toungoo) to Vith Loikaw. The Chinese Vth Army would defend Pyinmana and Vith Loikaw. But by now 'Vinegar Joe' Stilwell had poisoned relations between himself and the British to such an extent that both sides thought that the other would collapse in front of the Japanese advance. On 1st April Lieutenant-General Slim was visited by Generals Wavell and Alexander at Allanmyo, Corps HQ, 35 miles north of Prome, while, on the same day, the 17th Indian Division around Prome was finally driven out.

The 7th Armoured Brigade were in action on 2nd April, as part of the rearguard and the 2 RTR Stuarts ferried 2,500 infantry over 15 miles in 8 hours. Often the tanks had to tow each other out of dried river beds on their way to Dayindabo. It was the hottest season of the year with midday temperatures between 110 and 120 degrees Fahrenheit. By now the Japanese foul reputation for atrocities was being seen when twelve wounded British soldiers and marines were captured in Padang village and were tied to trees and bayoneted. Elsewhere a tank crew of 7th Hussars on outpost duty were offered eggs and chickens by Burmese villagers, who prompt drew out their dahs and promptly cut down three troopers, taking the opportunity to change allegiance as the great British Raj was apparently crumbling.

By now 7th Hussars's tank strength was down to thirty-eight and many B vehicles had been lost to enemy action and bombing. Lieutenant-Colonel Yule was now CO of 2 RTR, acting as rearguard. On the evening of 7 April near Myaungbintha, 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR (under Major Bonham-Carter) fought an action against three enemy vehicles, which may have been captured Stuarts, and hit them all. On 11th April, 7th Hussars' patrol sighted a captured Stuart flying a Japanese flag, but unfortunately out of range. For over a week Lt-Gen General Slim awaited the arrival of a Chinese regiment to garrison Taungdwingyi, but in vain, despite Stilwell's promise and with 48th Indian Brigade and 7th Armoured Brigade at Kokkogwa 10 miles west of Taungdwingyi, he moved his Corps HQ to Magwe on 8th April.

The battle for the vital oil fields started on 11th April and continued for a week and one of the most desperate actions was against 48th Indian Brigade at Kokkogwa. The enemy attacked fanatically and in strength on a pitch-dark night lit by violent thunderstorms. At dawn on 12th April 'B' and 'C' Squadrons, 2 RTR, were in action and the tanks, according to General Slim, 'moved out to a good killing'. Unfortunately, some of the 7th Hussars' tanks captured in the Shwedaung battle had been repaired and went into action with Japanese crews. 2 RTR were again in action near Magwe and had brisk actions at Thadodan and Alebo.

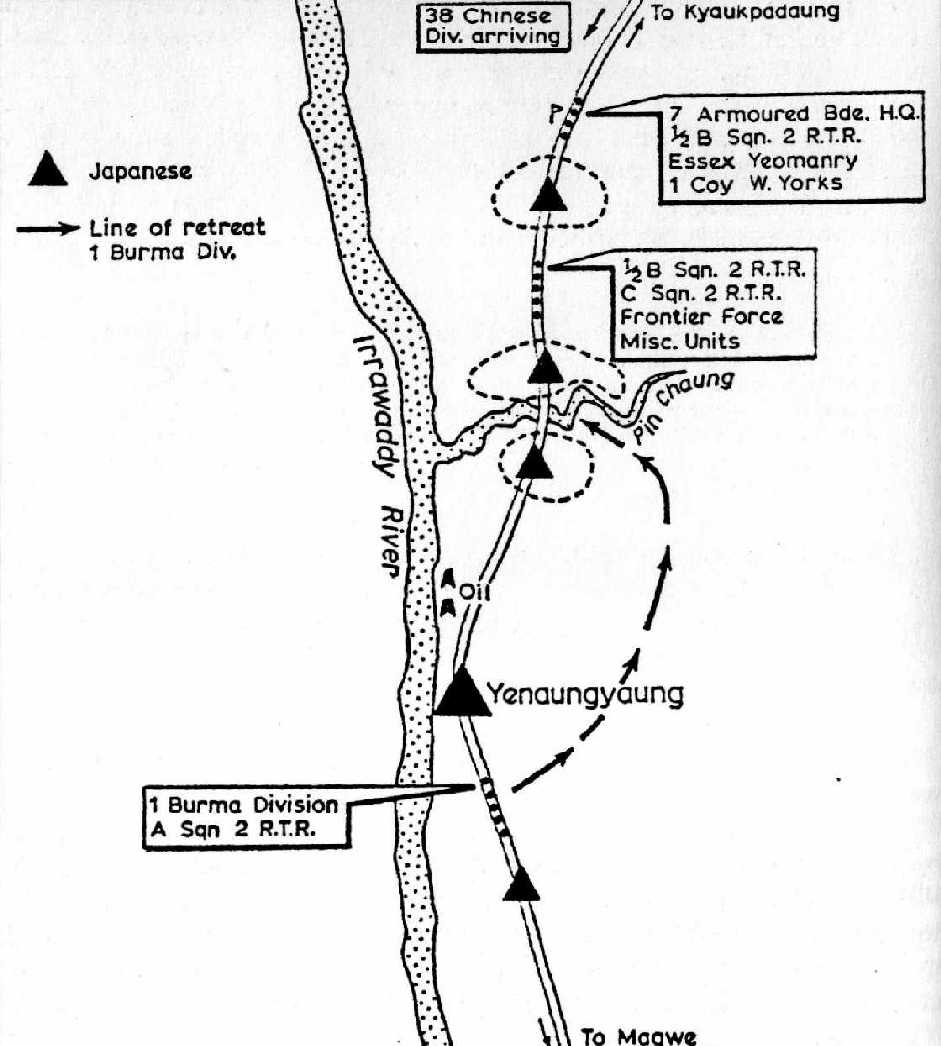

From 13th to 17th April 1942, 2 RTR were kept busy day and night. They ferried the KOYLI (2nd Battalion, The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry) up the main road to Milestones 310, then 336 and killed 50 enemy in the village of Tokson and one tank was destroyed when it was hit six times at very close range by a 75mm gun. On several occasions a dangerous alternating sandwich situation occurred as Japanese roadblocks split in three a force consisting of elements of the Burma Frontier Force, 1st Burma Division, 7th Armoured Brigade HQ and of course 2 RTR. At one stage the situation was so critical that General Alexander 'asked' Lieutenant-General Joe Stilwell to move the Chinese 38th Division 'at once' into the Yenaungyaung area. The British and Indian troops found that the Japanese frequently dressed in the uniform of the Burma Rifles or as civilians and making it difficult to tell friend from foe.

General Alexander wanted to keep the

unenthusiastic Chinese 'on side' and

insisted that Lt-Gen Slim keep the 17th Indian Division in and around Taungdwingyi.

For the next two days the 1st Burma Division, whose 1st Burma Brigade had

suffered heavy casualties, pulled back in good order,

covered by tanks of 7th Armoured Brigade, to the Yin Chaung watercourse, where

three

Chaungs - Pin, Kadaung and Yin - all flowed from east to west to join the

Irrawaddy. The battle of Yenaungyaung turned out to be a disaster fought in an

area of about 20 square miles formed to the north by the Pin Chaung and the

south by the Yin Chaung. The Japanese 33rd Division had cut the Magwe road

between Slim's two divisions, who were about 50 miles apart, 1st Burma Division

retreated northwards bombed and machine-gunned by the Japanese air force. Lt-Gen

Slim

wrote; '7th Armoured Brigade again covered the withdrawal; what we should have

done without that brigade I do not know.'

General Alexander wanted to keep the

unenthusiastic Chinese 'on side' and

insisted that Lt-Gen Slim keep the 17th Indian Division in and around Taungdwingyi.

For the next two days the 1st Burma Division, whose 1st Burma Brigade had

suffered heavy casualties, pulled back in good order,

covered by tanks of 7th Armoured Brigade, to the Yin Chaung watercourse, where

three

Chaungs - Pin, Kadaung and Yin - all flowed from east to west to join the

Irrawaddy. The battle of Yenaungyaung turned out to be a disaster fought in an

area of about 20 square miles formed to the north by the Pin Chaung and the

south by the Yin Chaung. The Japanese 33rd Division had cut the Magwe road

between Slim's two divisions, who were about 50 miles apart, 1st Burma Division

retreated northwards bombed and machine-gunned by the Japanese air force. Lt-Gen

Slim

wrote; '7th Armoured Brigade again covered the withdrawal; what we should have

done without that brigade I do not know.'

At 1300 hrs on 15th April 1942, Lt-General Slim gave the fateful orders for the demolition of the vital oil fields and refinery. The oil wells were stopped with cement, although the Japanese later were able to tap supplies by re-drilling the wells. The Allies watched a million gallons of crude oil burning with flames rising five hundred feet and all over the area there hung a vast, sinister canopy of dense black smoke. To those watching it, it was both a fantastic and a horrible sight.

The Stuart tanks of 7th Armoured Brigade had now long since exceeded the track mileage laid down for workshop attention. Nevertheless on 16th April, 2 RTR did sterling work ferrying back the exhausted infantry picking up the wounded and constantly counter-attacking to delay the advancing enemy. Moreover 2 RTR were the only reliable communication available to General Bruce Scott (1st Burma Division) and his harassed brigade commanders. Two tanks were lost but it is virtually certain that without the brilliant work of 2nd Bn. Royal Tank Regiment, 1st Burma Division would never have got clear of Magwe. That evening Slim ordered most of his precious 7th Armoured Brigade to withdraw through Yenaungyaung to beyond the Pin Chaung. Now the arrival of the Chinese Lieutenant-General Sun Li Jen, commanding the 38th Infantry Division at Slim's HQ, was much welcomed. However, the Chinese had no artillery or tanks of their own and Lt-Gen Slim decided to offer what artillery and tanks he could, to support Sun's attack. Brigadier Anstice, commanding 7th Armoured Brigade, rose to the occasion and he and Lt-Gen Sun got on famously together, mainly as Slim had privately told Sun, inexperienced with tanks, always to consult with Anstice before employing them. By now Lt-General Slim's only link with Major-General Bruce Scott (GOC 1st Burma Division) was by radio from 7th Armoured Brigade HQ to the command tank of 'A' Squadron 2 RTR.

During the fighting, 'C' Squadron, 2 RTR were part of a small mixed brigade supporting the Chinese infantry division in the area of the Magwe oil fields. The Chinese had marched several hundred miles from Mongolia down the Burma road. Having discussed tactics it was agreed that 2 RTR tanks would carry 10-15 soldiers on each tank, then penetrate as far into the jungle as possible before dropping them off and covering their attack with all tank weapons and RHA 25-pdr guns. 2 RTR's medical unit concentrated on helping wounded soldiers and the Chinese were most grateful for this help, which was mostly just bandages and some iodine. For their part in the actions at that time Major Mark Rudkin MC (commanding 'C' Squadron), Captain Plough and four other officers and NCOs of 2 RTR were subsequently awarded the Chinese Medal of Honour. For the next three days the Chinese 38th Division, with 'B' and 'C' Squadrons, 2 RTR, attacked southwards and 1st Burmese Division with 'A' Squadron 2 RTR attacked northwards and on 19th April the two divisions met near the Pin Chaung river after heavy casualties on both sides. 'A' Squadron put up a magnificent fight and probably saved 1st Burmese Division from being overrun and their commanding officer, Major N. Bourne, was subsequently awarded the DSO. For the next week 'C' Squadron, 2 RTR, and a troop of Essex Yeomanry 25-pdrs remained with 38th Chinese Division for a week and the tanks of 2 RTR carried many of the wounded infantry in their Stuarts.

Meanwhile, led by their GOC, Major-General Bruce Scott, 1st Burma Division formed up in a column, with guns in front, wounded in ambulances, trucks next, with a spearhead of Stuart tanks and infantry until the track turned to sand, and with abandoned transport the Division fought their way to and across the Pin Chaung. Once there the survivors concentrated around Gwegyo. On 19th April the Chinese 38th Division, thrilled with tank and artillery support, took Twingon, a key suburb of Yenangyaung, rescuing 200 prisoners and wounded men from 1st Bn. Inniskilling Fusiliers. On the next day with 2 RTR they put in such an attack on the rest of Yenaungyaung and Pinchaung that the Japanese suffered heavy casualties. But the Allied forces were too weak to hold the oil fields and were obliged to retreat, 1st Burma Division was withdrawn 40 miles north to the Mount Popa region to reorganise, having lost most of its equipment, with 7th Armoured Brigade covered its withdrawal as usual.

At a meeting with General Alexander, Stilwell and General Slim on 19th April it was decided that 7th Armoured Brigade and one brigade group of 17th Indian Division would go to Lashio with Chinese Vth Army, but the Japanese onslaught on the 20th and 21st practically destroyed the Chinese VI th Army, which simply vanished, and the bulk of V th Chinese Army became involved in scattered, confused fighting, so the plan was abandoned.

Final Stand in Burma: On 23rd April 1942 revised plans were drawn up for the defence of Burma, with 17th Indian Division and the remnants of 1st Burma Division to stand astride the Chindwin River to cover Kalewa and 7th Armoured Brigade, with 38th Chinese Division to hold from the Mu River to the Irrawaddy River. However, Lt-Gen Slim noted that if the evacuation of Burma became necessary some British forces, including 7th Armoured Brigade, would accompany the Chinese forces back into China. It is probable that none of the Desert Rats in Burma were aware of this possibility. Lt-Gen Slim then immediately ordered 7th Armoured Brigade with all speed to Meiktila, 70 miles north-east of Yenangyaung, and on the 25th, east of Meikfa, where they surprised an enemy armoured and mechanised column and 'shot it up' with considerable loss to the Japanese. During this period 'C' Squadron, 2 RTR, stayed with the Chinese 38th Division until the 26th, acting as their rearguard. On their last day about eighty-five members were each presented with one rupee by the grateful (and impoverished) Chinese unit. The commander of 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR (Major Bonham-Carter) set off for Pyawbee with two scout cars to meet the Chinese and a mile from the town he suddenly encountered three Japanese tanks 75 yards away, but their fire was much too wild. At about the same time a troop of 7th Hussars ambushed a column of enemy transport on the Toungoo road and wrecked most of them.

In Kadang 'A' Squadron, 2 RTR, helped the West

Yorkshires occupy the village during a hard-fought day. On the 27th both 7th

Hussars and 2 RTR withdrew into leaguer north of Wundwin. However, the next

morning 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR, passing through Ngathet and lost two Stuarts to

a group of four enemy anti-tank guns, while later the same morning a group of four enemy tanks were

engaged by the Essex Yeomanry and several were hit.

Throughout the day enemy infantry with armour support were infiltrating around

Ngathet and Shanbin nearby. Brigadier Anstice instructed Lieutenant-Colonel Yule

to keep in action while 7th Hussars and 'C' Squadron, 2 RTR, carried most of the

63rd Brigade troops to safety on their tanks, with this ferrying operation on tanks and Essex Yeomanry gun limbers

continuing throughout the night. The

next morning a Troop from 'C' Squadron troop, 7th Hussars, encountered another

enemy transport company and destroyed half of them, but elsewhere a Japanese dive bomber

destroyed a Stuart in another troop.

In Kadang 'A' Squadron, 2 RTR, helped the West

Yorkshires occupy the village during a hard-fought day. On the 27th both 7th

Hussars and 2 RTR withdrew into leaguer north of Wundwin. However, the next

morning 'B' Squadron, 2 RTR, passing through Ngathet and lost two Stuarts to

a group of four enemy anti-tank guns, while later the same morning a group of four enemy tanks were

engaged by the Essex Yeomanry and several were hit.

Throughout the day enemy infantry with armour support were infiltrating around

Ngathet and Shanbin nearby. Brigadier Anstice instructed Lieutenant-Colonel Yule

to keep in action while 7th Hussars and 'C' Squadron, 2 RTR, carried most of the

63rd Brigade troops to safety on their tanks, with this ferrying operation on tanks and Essex Yeomanry gun limbers

continuing throughout the night. The

next morning a Troop from 'C' Squadron troop, 7th Hussars, encountered another

enemy transport company and destroyed half of them, but elsewhere a Japanese dive bomber

destroyed a Stuart in another troop.

At Kyaukse 7th Hussars and 48th Brigade were in a good defensive position, with mountains on one side, the Sittang Marshes on the other, and along with a Gurkha battalion spent the 28th to the 30th in action every day. Here, two tanks were lost and 10 men killed, but 150 Japanese were accounted for and 12 enemy lorries captured. The 63rd Brigade, of 17th Indian Division, around Wundwin were bombed heavily, but the Desert Rat Stuart tanks held back strong enemy infantry and artillery groups, including some light Japanese tanks, which when engaged scuttled back to shelter. For many the action at Kyaukse was a really brilliant example of rearguard work, but the decision had now been taken officially for a withdrawal back into India across the Irrawaddy River, not only of General Slim's Corps but Gen Sun's 38th Chinese Division. On 28th April the Corps orders stressed that 17th Indian Division would cross the Irrawaddy River by ferry and boat and 38th Chinese Division and 7th Armoured Brigade would hold the east bank of the river from Sagaing to Ondaw. The great Ava Bridge had been allotted to 7th Armoured Brigade along with V th Chinese Army. On 28th April they started to cross over and, as the last tank of 7th Hussars crossed, the bridge was blown up to cut the main road. As the Brigade crossed the Ava Bridge, a notice said that the maximum weight was six tons and a Stuart weighed thirteen tons. Slim was told the name of the British engineering firm who had built the bridge and reckoned they had built in a safety factor of 100 per cent. However, Lt-Gen Slim ordered the Stuarts across one by one. The centre bridge spans were blown at midnight on 30th April and with Burma was lost.

Crossing the Chindwin and back to India: The glamorous city of Mandalay had been devastated by Japanese bombers. It was full of deserted dumps, stores and camps of every kind including a dump (supposedly guarded) of high octane fuel for the Stuart tanks. A 'supposed' Burma Army Colonel had ordered it to be destroyed and it was. So the next dreary retreat started. The advent of the heavy monsoon rains due on about 20th May was a key factor. The allies route northwards would run through Ye-u to Kaduma, 20 miles north-west and then into the jungle for 120 miles until the Chindwin River was reached at Shwegyin. Then a 6-mile river journey up-stream to Kalewa, along the Kabaw valley through jungle to Tamu to reach a road that might link Imphal to Assam. The British and Indian commanders knew that it would be an impossible march if the monsoon came before they had completed this part of the withdrawal.

Monywa was a vital river port on the Chindwin River 50 miles west of Mandalay. It was vital because if captured by the Japanese they could use the river to outflank the British, Indian and Chinese Allied forces. A reasonable road and railway went through the town on the east bank of the river. Lt-Gen Slim's HQ was 16 miles north, but on 30th April a sudden attack by 33rd Japanese Infantry Division from the west bank of the river, marching north after their capture of Yenangyaung, established a bridgehead on 1 May. The HQ of 1st Burma Division was overrun and Lt-Gen Slim ordered all available units to counter-attack. 7th Armoured Brigade supporting the 38th Chinese Division on the Irrawaddy line were sent post-haste to the rescue, travelling at night via Ettaw for a 140-mile march.

'C" Squadron, 7th Hussars, separately came up from the south with 63rd Indian Brigade to help and lost two tanks in the process. 2 RTR then acted as rearguard during the slow withdrawal to Ye-u where Generals Alexander and Stilwell were quartered. Lt-Gen Slim sent in a counter-attack on 2nd May to recapture Monywa by the 1st Burma Division, which was thwarted by vigorous Japanese defence in the town and from motor launches in the Chindwin River. Unfortunately a radio message, apparently from a senior officer of Brigadier Anstice's staff to 13th Indian Brigade who passed it onto to 1st Burmese Div HQ, ordered the whole division to pull out and withdraw to Alon, which it did. The 7th Hussars covered the withdrawal as using two troops from 'C' Squadron in a series of leap-frogs to cover the withdrawal and only encountered slight problems from mortars and a few rounds of anti-tank fire. Three members of 'A' Squadron, 7th Hussars, were stabbed to death by Burmese dacoits, but the Squadron and West Yorkshires returned to take a terrible revenge. The roads were a horrible sight crowded with civilian refugees many of whom had been killed by dacoits, as the Burmese had been quick to take their revenge on Indian shopkeepers and moneylenders.

On the same day, 2nd May 1942, 2 RTR were widely dispersed over a 50-mile triangle, now concentrated at Budalin. As the regiment withdrew at very slow speed up the road from Monywa for the next four hours, its speed was governed by the marching infantry in front who had animal transport with them. One Stuart tank shed a track in heavy going and a tank from 'C' Squadron was left to guard it while the crew effected repairs. At 04:00 hrs tanks were heard moving towards the RTR leaguer. The NCO commanding the guard tanks in the leaguer assumed they were the stragglers returning. Just as he heard excited Japanese voices inside one tank (a captured Stuart) it shot at and set on fire a genuine RTR tank, which burned killing the crew. The road to Kalewa was only about 12 feet wide, through thick and hilly country and in many places there were ravines on one side and the surface being soft many vehicles were lost over the side. Broken down vehicles were also pushed over the side to keep the road clear. There were many sharp corners and many soft river beds. The many inexperienced drivers in the column added to the hold-ups and breakdowns. Eventually after 24 hours in which we covered 54 miles, the regiment formed a leaguer about eleven miles from the ferry on the Chindwin. Over the past eleven weeks there had been little time had been spent on maintenance during which many tanks had covered 2,400 miles. As the column moved on 2 RTR lost more tanks, one falling into a Chaung in the dark, another on 4th May by enemy action around Budalin. Three more tanks had engine seizures beyond hope of repair and were abandoned after being destroyed on 6th May 1942. The Japanese claimed that in the retreat from Monywa the Burmese Division had suffered 1,200 casualties, 2 tanks and 158 vehicles.

There were 2,300 wounded Allied soldiers not yet evacuated from Shwebo, 50 miles north-east of Monywa. The rearguard continued their retreat through the huge teakwood forests towards Kalewa ferry on the Chindwin River, averaging 12 to 15 miles a day, with the remaining Stuarts and 7th Armoured Brigade transport helping to ferry the troops. The whole Corps reached Shwegyin, a so-called river port, without a direct crossing over the Chindwin. From here River steamers had to sail four miles upstream to Kalewa, unload and return, which was a journey of several hours. The Japanese 33rd Infantry Division, under General Sakurai, had embarked a flotilla of forty launches from Monywa towards Shwegyin upstream and arrived on 10th May. Lt-Gen Slim got all of 1st Burma Division across the river, with the help of booms and vigorous defence of the 'basin', a horseshoe-shaped flat space surrounded by sheer 200-foot escarpment around the loading pier. Despite heavy Japanese bombing, Gurkha battalions held off determined enemy attacks, while the British 25-pdrs were brought down to the water's edge and kept firing to the last moment before they were ferried upstream. After a huge last barrage the remaining guns and tanks were destroyed. However, 28 guns, 80 of the best mechanical transport and 4-wheel lorries, were saved, but the loss of 70 tanks was a terrible blow. It was true that the Stuarts of 7th Armoured Brigade were worn out, obsolete, and hard to replace in India, but they held such a sentimental place in the esteem of the the men for what that owed them so much and their crews that it was like abandoning old and trusted friends to leave them behind. On the way to the Chindwin they had smashed through twenty roadblocks and lost forty tanks in the process. The 7th Hussars had lost thirty-three officers and men killed in action and a similar number wounded. 2 RTR have seventeen killed in action buried in St George's Church, Mingaladon.

It was a bitter moment for both tank battalions. They had lost forty-five tanks in the eleven-week campaign, about half to enemy action and half to accidents (mainly toppling into deep chaungs) or mechanical failure. 2 RTR, noted that the Japanese weapon which did most damage was their 50mm mortar, which they used this with extreme accuracy and they penetrated the top of the tanks where the armour was thinnest. On one occasion a tank of 'B' Squadron stopped for a few moments in an open bit of ground and within one minute received six direct hits. The Japanese 75mm gun used over open sights was fairly effective and stopped a tank but this did not penetrate the frontal armour, but it often penetrated the side or rear and would only damage the front. About a quarter of the tanks hit by 75mm guns were knocked out.

The commanding officer of 'A' Squadron, 7th Hussars (Major Llewellen Palmer) persuaded a ferry-boat captain to tow a Stuart tank, bizarrely named 'The Curse of Scotland', across the river on a raft, which he did, but the ferry-boat crews threatened to strike if ordered to tow another. Later, stripped of its turret, this tank became the command vehicle of the Indian 7th Light Cavalry. The remaining seventy tanks were destroyed with sledgehammers and by having the engine sump and radiator drain plugs were removed while the engines were run at high revs until they seized up. Optical equipment, radios and wiring were smashed, ammunition was taken away and buried. A week had been allowed for the Chindwin crossing but Shwegyin was a deadly bottleneck once the Japanese had fought their way up to the escarpment overlooking the basin. The six river steamers could carry 500 or 600 men packed tight at a time and no more than one lorry, two or three guns and a jeep or two, but no tanks. The 7th Hussars officers wore their distinctive crossbelts and Padre Metcalfe took sufficient prayer books for a full-scale service to be held on arrival in India.

The monsoon rains started on 12th May bursting with a torrential downpour and soon Lt-Gen Slim's survivors were marching on foot. The men of 7th Armoured Brigade were organised as infantry rifle battalions for the 90-mile slog from Kalewa through the Kabaw Valley to Tamu on the Indian border. All ranks carried their rifles and revolvers and some had Tommy guns. Rations had been issued to all ranks and they started the march to Imphal in an organised column with a few of their own vehicles. The going was rough through the foot hills of the mountain range with many small rivers to cross. This kept the men clean after the humid and hot days of the march. It was chilly and often very wet, but on half rations, marching in the morning and evening to avoid the heat of the day, they reached India on 15th May 1942. Fever was rampant, food and drink short and climbing the hills on foot on tracks inches deep in slippery mud and soaked to the skin was an ordeal, but fortunately, low clouds had kept the Japanese Air force away. South of Tamu Indian-driven lorries drove south to meet the columns, but when the drivers saw the survivors they were so frightened they took their lorries into the jungle and hid. To stop this happening again each driver had a man from 7th Armoured Brigade assigned to them who saw to it that the Indian drivers went where they were told.

After reaching Indian, the Brigade stayed for a week, alternately marched or were ferried by lorries, on a barren hillside at Milestone 108, called 'Dysentery Hill'. Lorries then arrived to ferry the Desert Rat 'infantrymen' to Imphal and on 25th May by lorry to Manipur, thence by cattle truck, train and bus to Ranchi to be met by Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Broad. It is a fitting epitaph to the courage and professionalism of 7th Armoured Brigade that in his dispatches General Alexander wrote; 'The 7th Armoured Brigade showed the value of disciplined, experienced troops. They retained their fighting qualities and cheerful outlook throughout.'

India and then to Iraq: The two Regiments 7th Armoured Brigade, 7th Hussars and 2 RTR without tanks recuperating in India and in June of that year the brigade came under command of the 32nd Indian Armoured Division. After casualties and sickness their strength had dwindled to 1,500 men. The next month they were inspected by the Duke of Gloucester at Dhond and some General Grant tanks, Bren-carriers and armoured cars arrived. Here they were joined by there old friends from 414 Battery (Essex Yeomanry) RHA, who by now had helped form the new 14th RHA Regiment. By September the brigade had absorbed reinforcements, was reasonably proficient with its new equipment and then they started on a curious odyssey. It would be another two years before they fought again. While a few individuals stayed on as instructors at the Indian Armoured Corps Depot at Ahmednagger, on 21st September the brigade set sail from Alexandria docks in Bombay on HMT Neuralia, with their tanks aboard HMT Risalder and HMT Belray. General Wavell visited the brigade before they left India as he had known them in North Africa and commented that the formation was the finest in any command he had held. Nine days later they reached the mouth of the Shat el Arab, Iraq, and moved upstream to Margil, disembarking on 2nd October before travelling by train to Zubair. Tactical exercises were carried out between Hammadiya and Latafiya and it was during these exercises 2 RTR code names were used, which stuck and have been used ever since: HQ Squadron - Nero; 'A' Squadron - Ajax; 'B' Squadron - Badger; 'C' Squadron - Cyclops; and Recce Troop - Huntsman

The 7th Armoured Brigade's time in India and Burma was over, but what was to become the longest campaign ever fought by the British Army had started and would last until the Japanese surrender in August 1945, not long after Rangoon had been retaken in June the same year. Many units the Brigade had served with during the long retreat of 1942 were to be part of the recapture of Burma. Their story and that of the 14th Army should not be forgotten.